Onyong

Sketch of Onyong by Robert Williams (then aged 13), reproduced from Tales From Ngambri History, 2003.

Our Ngambri ancestors were the custodians of the country south-west of Weereewaa (Lake George), which includes the modern Australian Capital Territory. The name of the capital, Canberra, derives from that of our ancestral group.

The population of the combined Ngambri and their neighbouring kin group, the Ngurmal, was reduced from 1000 or more to about 50 only 40 years or so after the first white invasions and also as a result of invasions from neighbouring Ngambri enemies.

The Ngambri leader at the time of the first white invasions was Onyong. The Ngambri combined with the remaining Ngurmal and their leader, Noolup, from the 1830s.

Onyong died in 1852 and is buried on a hill that bears his name in the Tharwa region. Noolup died in a cave at Booroomba Rocks in 1860.

The hillside below marks the burial place of Onyong, a Ngambri-Ngurmal Walgalu elder and warrior who lived in this area. Ngambri country stretches from south-west of Weereewaa (Lake George) to Kiandra and the upper Murrumbidgee, down the Goodradigbee River to the south Yass Plains, south of the Yass River through Ginninderra and Gundaroo and across Canberra and Queanbeyan to the Gaurock Ranges. Onyong was born at Allianoyonyiga Creek at Weereewaa (Lake George). Since he visited Goulburn frequently during his lifetime, this district may have been part of his mother’s country. It is most likely that local Europeans referred to him as ‘Onyong’ as they were unable to pronounce his full name, Allianoyonyiga. Many Aboriginal people were named after the places where they were born.

Onyong formed a life-long friendship with Garrett Cotter, an Irish convict who worked for a number of European settlers at Weereewaa. This friendship possibly deepened after Cotter was exiled to the west of the Murrumbidgee, now known as the ‘Cotter Reserve’, for allegedly stealing a horse (it was never proven!). Cotter was the first white man to live on that side of the river.

Onyong guided Cotter throughout the river corridor and introduced him to traditional Aboriginal routes through the mountains and alpine pastures suitable for cattle. Cotter advised other stockmen of these routes, saving them many days travel around the mountains.

Onyong lived in Cotter’s hut at his property, The Forest, in the Naas Hills just before he passed away c. 1852. On returning to Cuppacumbalong for a visit, he got involved with a fight for leadership with his old friend and countryman, Noolup (also known as Jimmy the Rover), and was killed.

Young William Wright, whose family then owned Cuppacumbalong station, witnessed the burial of this noble Ngambri elder. When he was an elderly man, Wright recalled vividly his memories of that day and described the traditional ceremonies associated with Onyong's death:

The men of the tribe...tied (Onyong’s body) up in a complete ball...His grave...on the top of a rocky hill...was about five or six feet in depth. A tunnel six feet in length was excavated and his body was inserted, with his spears (broken in half), his shield, his nulla nulla, boomerang, tomahawk, opposum rug and other effects. Then the hole was filled with stones and earth.

Today, Onyong is still honoured as a Walgalu warrior and leader by local Aboriginal families of Ngambri and Ngurmal descent.

Sketch of Onyong by Robert Williams (then aged 13), reproduced from Tales From Ngambri History, 2003.

Allianoyongiga (Onyong) monument. Plaque reads: “On this site Garrett Cotter built his first hut at ‘Naas Forest’ 1828. It was later occupied by his friend Aboriginal chief Hong-Yong.”

The best known survivors of the second generation of Ngambri, some of whom had a European as well as a Ngambri parent, were Bobby Hamilton, Nanny, Jimmy Taylor, Kangaroo Tommy, ‘Black Dick’ Lowe and ‘Black Harry’ Williams.

The Lowe Family at Lanyon, with King Billy from the south coast (standing left) and Nellie Hamilton, widow of Bobby, seated right with dog, circa 1896. King Billy was Nellie’s third husband.

From the De Salis Family Collection, reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Henry ‘Black Harry’ Williams at Uriarra Station, circa 1903.

Photo by George Webb, reproduced courtesy of the Webb Family of Fairlight Station

Henry Williams Street, Bonner, ACT

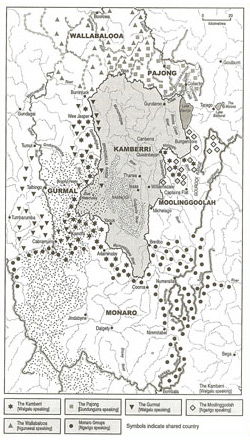

Our ancestral Ngambri country stretches from south-west of Weereewaa (Lake George) to Kiandra and the upper Murrumbidgee, down the Goodradigbee River to the south Yass Plains, south of the Yass River through Ginninderra and Gundaroo and across Canberra and Queanbeyan to the Gaurock Ranges.

Our ancestral Ngambri country stretches from south-west of Weereewaa (Lake George) to Kiandra and the upper Murrumbidgee, down the Goodradigbee River to the south Yass Plains, south of the Yass River through Ginninderra and Gundaroo and across Canberra and Queanbeyan to the Gaurock Ranges.

The map nearby shows core Ngambri (Kamberri) country with surrounding frontiers, of the 1820s-1880s. Symbols show shared country. It was compiled by Ann Jackson-Nakano from contemporary historical resources and reproduced here from The Kamberri, by Ann Jackson-Nakano, 2001. View larger map.

Ngambri country would have expanded and contracted over many generations before the European invasions as our ancestors fought with competing neighbouring groups and lost and regained country over thousands of years.

We Aboriginal peoples in south-east Australia were not limited only to our own country. In pre- and post-European times, as now, we travelled extensively, visiting each other’s countries, sometimes fighting, sometimes renegotiating country after battles, intermarrying, and hosting or attending ceremonial occasions.

Strict ceremonial routes were followed when we left our country to attend ceremonies elsewhere, and vice-versa.

The Ngambri had individual as well as group rights to country due to kinship connections and individual birthplaces. For example, Onyong was born in his mother’s country at Allianoyonyiga Creek on the eastern side of Weereewaa. Many Aboriginal children in our region were named for the place where they were born. Allianoyonyiga was Onyong’s birth name. It was shortened to Onyong because the whitefellers couldn’t say his birth name correctly.

By the mid-1880s the first generation of Ngambri who experienced the whitefeller invasion of our country had passed away.

The younger generations had never known a time when whitefellers did not occupy our country. By then, most of them were bilingual or multilingual, still able to speak their own and neighbouring languages as well as English.

They lived in two very different worlds. Ngambri men worked as stockmen and Ngambri women as domestics, but they continued to hold secret meetings up in the mountains and to host traditional ceremonies that continued to be attended by Aboriginal families from neighbouring groups.

Eventually, some Ngambri moved on to other areas, far away from their ancestral country, and intermarried with Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal peoples in those other regions.

A core Ngambri group remained, however, to take care of country.

Ngambri elders were still camping out at the caves at Yankee Hat when it was publicly declared that their ancestral country was to become Australia’s capital, and that the name of the capital would be Canberra – an Anglicised version of the Ngambri name.

Younger Ngambri worked as labourers on the building of the provisional Parliament House and on the reconstruction of Yarralumla Station, which became Government House.

There has always been a Ngambri presence in Ngambri country, and always will be.

This cave or rock is now known as Yankee Hat. It is in Namadgi National Park.

Yankee Hat paintings, reproduced courtesy of Canberra Tourism and Events Corporation.

Ngambri campsite, Redhill ACT.

Ngambri ceremonial stones, Namadgi. Photo by Reg Alder.

The Ngambri will always be here.

The members of the Walgalu (Ngambri and Ngurmal) belonged within the nation to one of two classes or sections, which were inherited through the mother. The Walgalu were divided into Eagle-hawk people and Crow people. The people of each of these groups were blood relatives and were not allowed to marry another member of the same group.

Legends concerning Eagle-hawk and Crow are widespread in south-eastern Australia. The basic story concerned Kannua (the Eagle man), who was short, thickset and dark-haired, and Waaku (the Crow man), who was tall and light-haired. As well as belonging to one class or section of a society, each person inherited a totem. This meant that each person has a special bond with a natural species, such as a bird, animal, fish or even a star (Venus).